The new season of ‘Stranger Things’ marks the long-awaited return of Netflix’s most popular series to the platform after the pandemic break. The wait has been worth it: the series has returned with renewed strength, without accusing the wear and tear of some of the moments of its third year, and with episodes that honor the fame of the production and its unique blend of teenage tragicomedy and eighties-inspired horror/science fiction.

The series has never hidden its references, neither cinematic nor those from the real world. For example, the protagonists played Dungeons & Dragons or disguised themselves as the characters of ‘Ghostbusters’ on Halloween, in reference to the success that these pop culture mastodons had at the time. And on the other hand, metalinguistic nods abound to horror classics, such as John Carpenter on the soundtrack, Stephen King in the general spirit, and ‘Nightmare on Elm Street in this new season.

On this occasion, the attention of ‘Stranger Things’ is partly focused on a wave of moral panic in the United States in the eighties, whose effects lasted for years and in some cases have not been completely blurred, as shown by the latest tactics of the new American media ultra-right. This is the Satanic Panic, a conspiratorial movement that marked for decades the image of role-playing games, video games, and rock.

The Multiple Tentacles of Satanic Panic

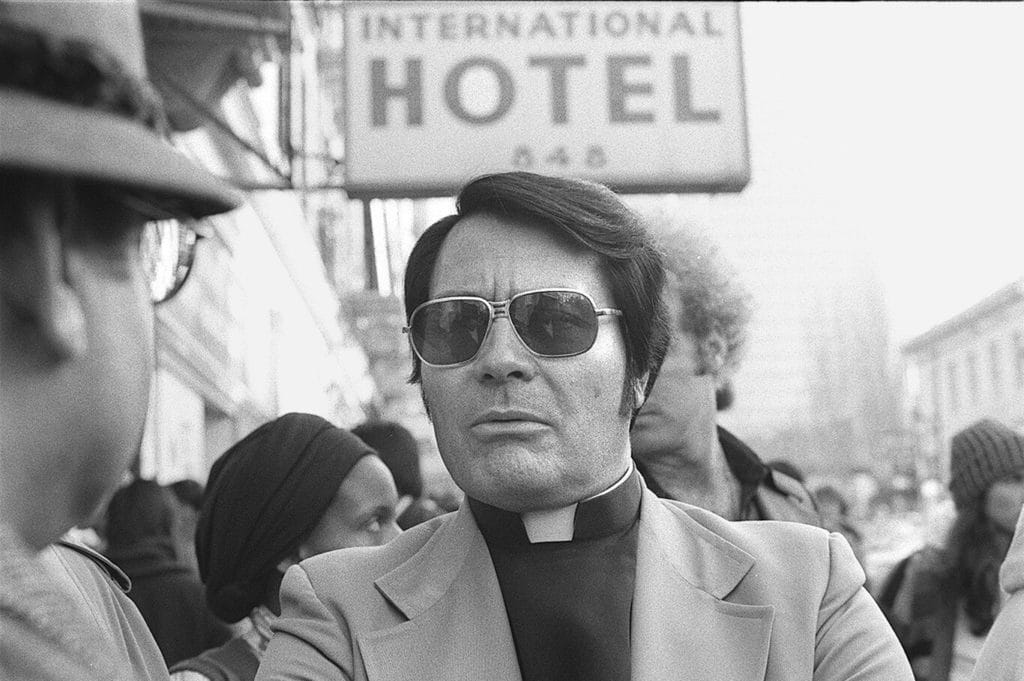

Essentially, satanic panic (or Satanic Panic, as it was known in the United States) encompasses a series of accusations (more than 12,000), unproven, of ritual abuses that spread in the United States in the eighties. It was at the beginning of these years when ‘Michelle Remembers‘ was published, a book by psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder in which he used a dubious technique of recovering hidden memories in which his patient (and, ahem, future wife) Michelle Smith brought to light a case of abuse in the context of a satanic sect and that he had forgotten because of trauma.

The popularity of the case led to a collective fear of the existence of satanic sects in the subsoil (and high political positions) of the country and led to other notorious cases spiritually linked to Pazder’s infamous book. For example, a series of accusations (hundreds of them) in 1983 to the McMartin nursery in California, falsely accused of child abuse, among other more folkloric things: that the managers were witches who took children flying around the city and that there was an intricate system of tunnels that connected nurseries around the country.

The media impact of this case (which ended with all the defendants acquitted in 1990, in what is the longest and most costly criminal conduct trial in U.S. history) generated its own moral panic over sexual (and satanic) abuse in daycare centers, but it is considered to be all part of the multiform Satanic Panic. Just as Qanon’s crackpot conspiracy theories and Hillary Clinton’s pizzeria messages are recent tailwinds of that thousand-headed hydra.

Thousands of trials were held that today, with the historical perspective, we consider within that enormous phenomenon that was the American moral panic of the eighties, but there was also a social impact, and that is what ‘Stranger Things’ reflects. Without going into plot details, there is a moment at the beginning of the season in which one of the most dubious young people in the area is accused of murder and satanic practices, without evidence (on the part, as always, of the wealthy inhabitants of the town).

Role-playing games and other satanic entertainments of youth

It is normal that a series that has always shown an overflowing love for Dungeons & Dragons (and that recovers in this season, for example with a sequence that equates the emotions and intensity of a game with that of a basketball game) ends up landing in the Satanic Panic. The mythical role-playing game was, along with heavy metal, horror films and video games, the great scapegoat for all the moral evils that the architects of the Satanic Panic shot from their buzzing little heads.

The appearance in 1980 of an expansion of the rules of Dungeons & Dragons entitled ‘Deities & Demigods’ angered the parents, who started a campaign against the role-playing game. One of the most notorious cases was the pamphleteering and extreme case of persecution of a high school role club in Heber City, Utah, with Christian pamphlets and all kinds of publications about the satanic and occult signs that hid the rules (which hide them as a wink, but that is the subject for another day).

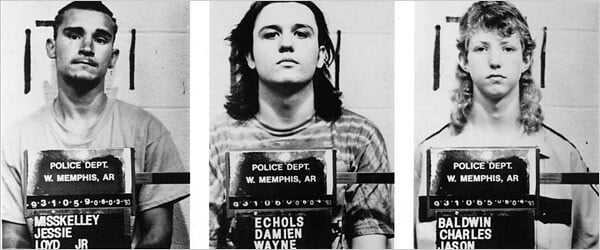

This aspect of the Satanic Panic – implicitly referenced in ‘Stranger Things’ – gave rise to one of its later manifestations, the trial of the three of Memphis, a media and legal persecution of three teenagers accused of killing a child, and whose only sin was basically to listen to Metallica and wear long hair in a town where they were not the norm. If you are interested in history, we highly recommend the trilogy of documentaries about the case ‘Paradise Lost’, plus a feature film produced by Peter Jackson, ‘West of Memphis’.

This last case is one of the most paradigmatic, and a good example of how dangerous moral panics can be: the three defendants were released in 2011 after 18 years in prison, after being convicted in very irregular trials, and where the boys pleaded guilty due to media and police pressure and interrogations that bordered on illegality.

The Satanic Panic, as you can see, was more than a momentary collective psychosis: it represented the fear that any neighbor might be carrying out aberrant acts under a gentle appearance. It is a phenomenon that connects with serial killers who marked a society obsessed with appearances, such as Zodiac or the Son of Sam, and who reach the delusions of the most crusty alt-right of today. This extraordinary vox article (the web, not our particular far-right humor) maps very well all its ramifications and most unsuspected manifestations of Panic and Satanic, and Stranger Things is the best example of the extent to which that paranoia at the national level has become part of the popular culture of our time.