It is known that someone has been transcendental in his specialty when the date of his death is used as a world commemoration of that specialty. Gary Gygax, creator of the most successful role-playing game of all time, ‘Dungeons and Dragons,’ died on March 4, 2008, the same date that serves to celebrate this hobby around the world.

But this commemoration was not born with the death of Gygax, but a few years earlier, in 2002, from an idea published in a specialized forum. That the death of Gygax occurred precisely on the same day that years, before he had set himself to celebrate the role, is a coincidence that borders on deus ex machina, and that leads not a few people to believe that Master’s Day commemorates the life of Gygax. But this is one more legend of those that surround the origin of D&D and that have settled with the passage of time. Like Gygax created the dragon and dungeon game alone, as we said in the previous paragraph (if you didn’t jump when reading it, this article will surprise you). The game that appeared in 1974 and was the work of Gary Gygax but also of a creator forgotten by the general public, Dave Arneson.

To correct this forgetfulness, which is not accidental, last year ‘Secrets of Blackmoor‘ was released, a documentary that exceeds two hours and raised 44,000 euros on Kickstarter. This vindicates the figure of Dave Arneson not only as co-author of the game – recognized as such in the first edition of D & D – but as a creator of concepts that today are the quintessence of the role. “Dave Arneson was the first master to say ‘What do you want to do?” says Griffith Mon Morgan III, co-author of the documentary with Chris Graves.

At first, it was all war

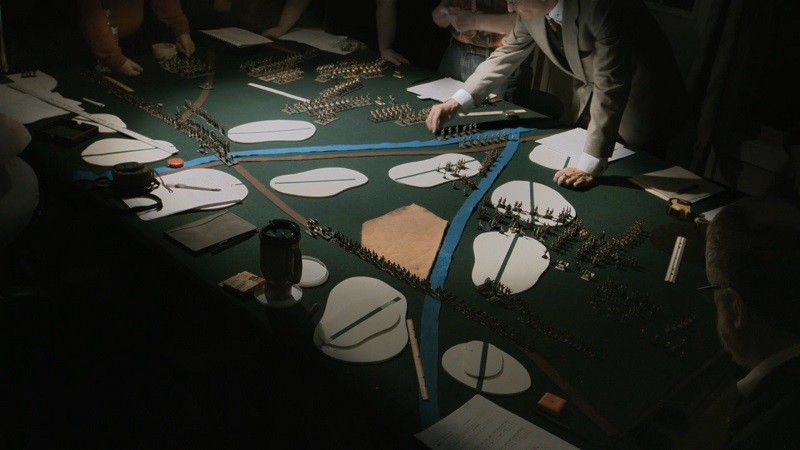

In the mid-60s, Arneson was a young man who worked as a security guard and lived with his parents in the city of Saint Paul, Minnesota (United States). Hundreds of Napoleonic soldiers were waiting in the basement of his house, as Arneson, like Gygax, was a fervent wargame player.

As a general of miniature armies, Arneson was not exactly of the Club of historical rigor. Arneson used to take some historical licenses because he liked to tell what could happen more than what actually happened, a practice is contrary to the canon of the wargames player, where it is usual to interrupt the game to find at what exact point on the table you have to put a plastic bell tower or a polystyrene hill so that the scale battle is as close as possible to the scenario you are trying to recreate.

In his playgroup, known as the Midwest Military Simulation Association (MMSA), Arneson wasn’t the only one licensed to invent. He was accompanied by David Wesely, a twenty-something who served as commander of the U.S. Army Reserve. Wesely used to make unthinkable proposals in the field of wargames. For example, faced with a river impossible to cross on foot, Wesely proposed creative solutions such as sending a detachment to a nearby town to get some woods with which to build rafts to cross the water.

Faced with that idea, a group of ordinary players would have suggested to Wesely that he take his troops and himself out of there and not come back, but MMSA players were used to this kind of eccentricity. In fact, they accepted with such enthusiasm the proto-tango stridencies of Wesely, that they invented the figure of an arbitrator to decide on everything that the rules did not cover, which was anathema in wargames because the usual thing was that if something was not regulated it could not be done.

Wesely’s Protorole

From so much Protorole, Wesely ended up jumping from wargame to role and created, in 1968, ‘Braunstein’ a scenario that recreated an imaginary city where Napoleonic troops met before starting the fighting. In this city, players did not assume command of armies, which was the usual tonic in a wargame, but of individuals: the mayor, a student, a swordsman, and a general. The characters had their own motivations and what happened in ‘Braunstein’ was built from the collective imagination of all the players. Of course, there were no attributes or skills, or rules designed for individual characters. It was all narrative.

The lack of rules was such that there was a duel between Arneson’s character and an opponent, and Wesely, who acted as the referee (or master if you prefer), had to decide the link of the match by throwing a 6-sided die. Arneson’s character died, much to Wesely’s chagrin, disenchanted with the death being so random, and to Arneson’s delight, who was happy to bring storytelling to the rules. By the way, in that game, perhaps one of the first role-playing games in history, there was already a player, Helen Nichols, as the documentary ‘Secrets of Blackmoor’ collects.

And what was Gary Gygax doing in the meantime, in the late ’60s? Gygax was engaged in his wargames and particularly in one, ‘Chainmail’, a medieval skirmish game he was writing with Jeff Perren that included rules for individual combats. ‘Chainmail’ will be fundamental for the future of the Gygax-Arneson relationship.

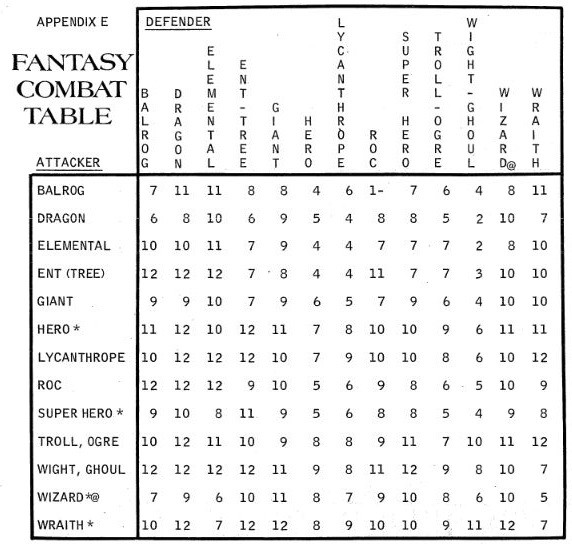

The first version of ‘Chainmail’ fit the realistic medieval imaginary, but Gygax soon added a fantastic expansion with dragons, lycanthropes, and fireball-throwing wizards, as well as a good number of creatures from Tolkien’s imaginary, such as ents, hobbits, and balrogs. This addition, surprising given that Gygax was not a reader of Tolkien but of pulp literature, aroused, quite sometime later, suspicions about possible plagiarism of a previous game.

This theory of plagiarism is not crazy, because the pecking in other people’s games was common among the players of the 60s, who published their systems in bulletins of stapled folios that were sent to each other by postal mail. “These games were a home hobby in those days and players would take things from numerous games to create their own,” explains Mon, co-author of the documentary Secrets of Blackmoor.

The first game of Blackmoor

But let’s go back to Arneson, who since the narrative experiments with ‘Braunstein’ had long been looking for rules of engagement outside the realm of wargames. In this search he came across the ‘Chainmail’ of Gygax and Perren and was immediately attracted to the fantastic part, motivated by the idea of not having to put up with those of the Club of the historical rigor of the wargames. ‘Chainmail’ contained rules for one-on-one combat and settled these disputes with matrices that decided who survived. Arneson studied these rules and decided to bring them to the table in his next game.

Such a departure happened in April 1971, in the usual setting, the basement of Arneson’s parents. The city where that particular ‘Braunstein’ would be played was not from the eighteenth century but a medieval fantasy village with a castle in the middle: Blackmoor. Arneson assumed the role of master and players parked their hussars and dragons to become dwarves and wizards.

This game was key for 37 reasons but we are interested in only four:

- The characters had attributes such as strength, courage, sex (?), and health, among others, something Arneson had already experienced in his own Napoleonic games to define some influential generals.

- The characters accumulated experience, which would help them improve those attributes in the following sessions.

- The characters had life points, so they could withstand more than one successful attack on them.

- Enemies would drop treasures when they were defeated by the characters. Thus, when a dragon was killed, gold coins, magic swords, and other treasures emerged that the dragon hid in non-visible compartments of his being.

Gygax calls Arneson to direct Blackmoor

Arneson was so amazed at Blackmoor that he did not hesitate to talk about the game and the news to everyone, and during the following months, he went to the only thing he played. He also told Gygax about it all, who invited him to his home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin (USA), to have Arneson lead a game of Blackmoor. Arneson agreed. We are talking about November 1972.

As He told Kotaku Rob Kuntz, Gygax’s friend and one of the players in that game, blackmoor’s session lasted all night. Gygax saw that Blackmoor had enormous potential and wanted to transform the game into a commercial game. Already in the morning, when Arneson was on his way home, Gygax and Kuntz himself tried to play (Kuntz as a master) but the thing did not finish flowing. After all, Blackmoor was in Arneson’s head and had been directing for months.

Gygax and Arneson created a primary version of D&D by exchanging postal mails and phone calls

So Gygax began to write down what he remembered from the departure a few hours ago and asked Arneson to send him his notes. This is told by Kuntz and also several people in the documentary Secrets of Blackmoor’. Arneson sent his notes, 18 pages almost full of monster statistics and notes related to rules of engagement that Arneson had merged from his own games and ‘Chainmail’. Gygax received the manuscript and when he had read half of it, Kuntz says, he said it was worthless and had to be rewritten. And they got on with it. Gygax and Arneson, by telephone and mail, wrote 50 pages of what in just a few months would become ‘Dungeons and Dragons’.

‘Dungeons and Dragons’ exceeds any expectation

After trying to sell the manuscript to some wargame publishers and receiving noes and strangeness, Gygax, who was still convinced that there was a business waiting, founded Tactical Studies Rules (TSR), together with Don Kaye, who put the money. That the company’s headquarters were the basement of Gygax’s house did not prevent these entrepreneurs from being granted the positions of president and co-founder (Don Kaye), director and co-founder (Gary Gygax), and creative director (Dave Arneson). Gygax didn’t want Arneson to be listed at the top of the TSR pyramid, which apparently didn’t matter too much to Arneson.

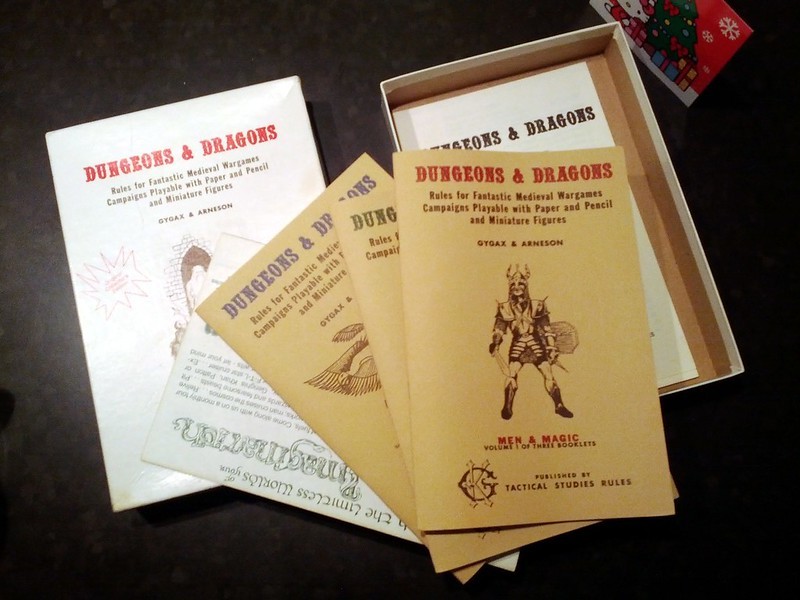

In 1974 they published ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ in the form of a box and booklets with a price of 10 dollars. They printed 500 copies and sold them in a few months and, as Arneson explained in Gamespy, a game of that style that sold 1,000 copies was already considered successful. The second reprint had 1,000 more copies that sold in a few months. The third reprint has already risen to 2,000. It was an unprecedented success. They maintained that dynamic for three years while releasing campaigns and books that expanded the setting. The first module was ‘Greyhawk’, Gygax’s campaign, and the second, ‘Blackmoor’, the campaign that Arneson continued to play with the Blackmoor Bunch (Blackmoor gang/group), as his Saint Paul players called themselves. The two campaigns came out in 1975.

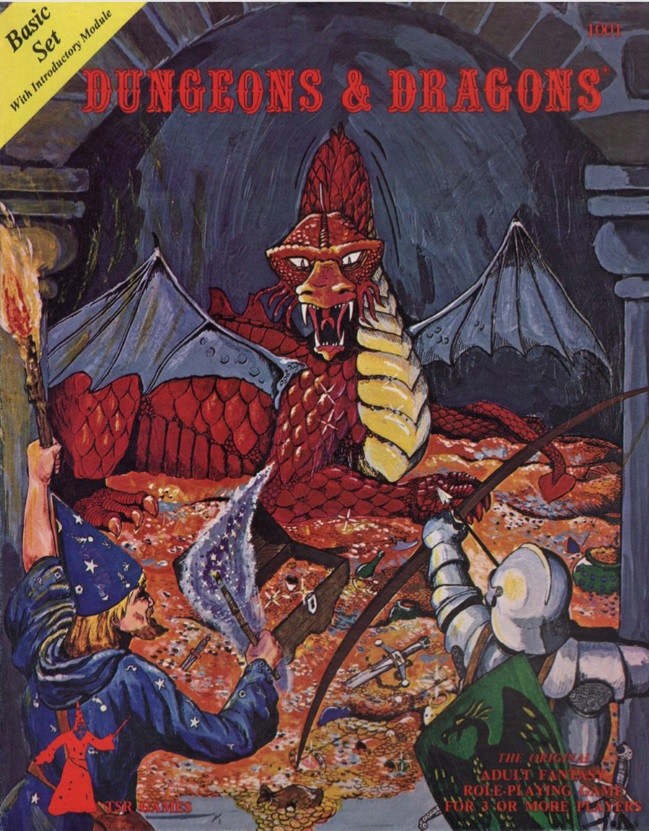

TSR published several games in those years but there were two milestones that marked the future of the young company and the couple Gygax and Arneson. In 1977 ‘Dungeons and Dragons, Basic Set’ was published, a revision of the original work, already with professional finishes, by Eric Holmes, professor of neurology and fantasy writer. The appearance of an alien creator was just one of the many inconsistencies that occurred in TSR. “Gygax and Arneson’s biggest failure was not understanding how the business actually works. They couldn’t see their game as the killer app of the time. What they really needed was to sell it while it had great value and let a bigger company take over,” Mon explains.

But the most serious incongruence, although it will be immediately understood why it was made, took place in 1978, when TSR unfolded the D&D line and inaugurated a new brand: Advanced Dungeons and Dragons (AD&D), which would be a very notable extension of the original work with many more rules (the main novelty) and that would establish forever the division of the game into three specific books: one for players, one for game directors, and one for monsters. Between ’78 and ’79 these three AD&D books were published, apparently incompatible with D&D. Authors? Only one: Gary Gygax.

Battle in the courts

When Arneson saw that his name was left out of AD&D and therefore would not collect the 10% royalties that corresponded to him for all publications related to D&D, he sued TSR in 1979 for plagiarism, since he considered that the new work was based on the one signed together by him and Gygax. Prior to Arneson’s lawsuit, Gygax himself had attempted to seize the exclusive rights to D&D by claiming it was based on Chainmail.

The dispute was resolved out of court and the details are not known, although Arneson did begin to receive royalties of 2.5% of everything produced for AD&D. Arneson parted ways with TSR and continued to write about Blackmoor. In 1979 he published his game ‘Adventures in Fantasy’, co-written with Richard Snyder, one of the members of the Blackmoor Bunch. In the mid-80s, Arneson again collaborated with Gygax on a series of modules for D&D (not AD&D) and soon after changed the role to the video game industry and teaching.

Gygax spent decades saying that Arneson’s Blackmoor was an expanded version of his ‘Chainmail’

Time has treated Gygax better than Arneson, although each did their part to make it so. While Arneson withdrew from the game and his name only came out when he went to court (the 1979 lawsuit was joined by four more, the last in 1985), Gygax was in front of the spotlight for decades, repeating that D&D was his work (it helped that his name appeared alone in the AD&D edition) and never stopped saying that Blackmoor was nothing but an expansion of ‘Chainmail’. And it’s not that it took years to start saying it. In the same introduction to the first D&D, in a text dated 1973, it already said that Arneson took ‘Chainmail’ to make Blackmoor.

For the co-director of the documentary ‘Secrets of Blackmoor’, that theory “is not based on any evidence” and while Arneson’s games at Blackmoor Castle already bore a lot of resemblance to what came out on D&D and published on his own Dave Arneson, “‘Chainmail’ is just a wargame,” says Mon.

In any case, what seems clear is that role-playing creation drinks from many sources, sometimes not conveniently accredited, and while it is rare to find current players who know who created the games they play, the vast majority of which are works published in the 70s and 80s, it is worth remembering from time to time those who laid the first stone of a hobby that gives so many hours of fun. And if the memory is for ‘Dungeons and Dragons,’ then we will have to think of two names: Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson.